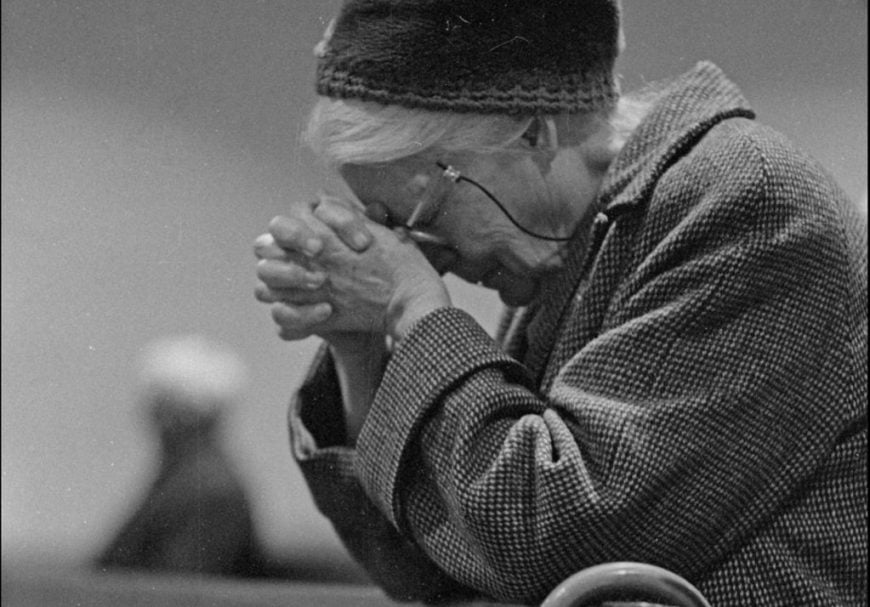

By Dorothy Day, as edited by Dan Lynch

“I wish every woman who has ever suffered an abortion would come to know Dorothy Day. Her story was so typical. Made pregnant by a man who insisted she have an abortion, who then abandoned her anyway, she suffered terribly for what she had done, and later pleaded with others not to do the same. But later, too, after becoming a Catholic, she learned the love and mercy of the Lord, and knew she never had to worry about His forgiveness. [This is why I have never condemned a woman who has had an abortion; I weep with her and ask her to remember Dorothy Day’s sorrow but to know always God’s loving mercy and forgiveness.] She had died before I became Archbishop of New York, or I would have called on her immediately upon my arrival. Few people have had such an impact on my life, even though we never met.” Cardinal John O’Connor

Dorothy Day died at age 83 on November 29, 1980. This article contains her actual words as edited and sometimes paraphrased by Dan Lynch. Her writings may be found at Internet site www.catholicworker.org.

I hobbled down the darkened stairwell of the Upper East Side flat in New York City. My steps were unsteady. My left arm held the banister tightly. My right arm clutched my abdomen. It was burning in pain. I walked out onto the street alone in the dark. It was in September of 1919. I was twenty-one years old and I had just aborted my baby.

Lionel, my boyfriend, promised to pick me up at the flat after it was all over. I waited in pain from nine a.m. to ten p.m. but he never came. When I got home to his apartment, I found only a note. He said that he had left for a new job and, regarding my abortion, that I “was only one of God knows how many millions of women who go through the same thing. Don’t build up any hopes. It is best, in fact, that you forget me.”

I wrote about this experience in my autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin. In my youth I had thought that the greatest gift that life could offer would be a faith in God and a hereafter. But then there were too many people passing through my life, – too many activities – too much pleasure (not happiness). The life of the flesh called to me as a good and wholesome life, regardless of God’s laws. What was good and what was evil? It is easy enough to stifle conscience for a time. The satisfied flesh has its own law. How much time I wasted during those years! I had fallen a long way from my youthful ideals. When I was fifteen, I wrote, “I am working always, always on guard, praying without ceasing to overcome all physical sensations and be purely spiritual.”

But these “physical sensations” allured me. I lived a social-activist Bohemian lifestyle in Greenwich Village, New York City. I think back and remember myself, hurrying along from party to party, and all the friends, and the drinking, and the talk, and the crushes, and falling in love. I fell in love with a newspaperman named Lionel Moise. I got pregnant. He said that if I had the baby, he would leave me. I wanted the baby but I wanted Lionel more. So, I had the abortion and I lost them both.

I later wrote in my autobiography, The Long Loneliness, “For a long time [after my abortion] I had thought I could not bear a child, and the longing in my heart for a baby had been growing.”

In 1924, I started a “live-in” relationship with Forster Batterham, an atheist and an anarchist. He believed in nothing except personal freedom to do as you please. We took up residence in a beach bungalow on Staten Island, New York. We foreshadowed the hippies of the sixties and lived a carefree lifestyle living off the land and sea – gardening, fishing and claming. I thought that we would be contributing to the misery of the world if we failed to rejoice in the sun, the moon, and the stars, in the rivers which surrounded the island on which we lived and in the cool breezes of the bay. Like Dostoevsky, I began to believe that the world would be saved by beauty. It was this beautiful, natural world that slowly led me back to God. “How can there be no God,” I asked Forster, “when there are all these beautiful things?”

However, I felt that my home was not a home without a child. For a long time, I had thought that I could not have a child. No matter how much one is loved or one loves, that love is lonely without a child. It is incomplete. Soon I became pregnant again. I saw this as a miracle from God because I thought that He had left me barren after the abortion. I wrote in a letter to a friend, “I always rather expected an ugly grotesque thing which only I could love; expecting perhaps to see my sins in the child.”

On the contrary, I gave birth to a beautiful daughter, Tamar Teresa, on March 3, 1927. I remembered that the labor pains swept over me like waves in the beautiful rhythm of the sea. When I became bored and impatient with the steady restlessness of those waves of pain, I thought of all the other and more futile kinds of pain I would rather not have had. Toothaches, earaches, and broken arms. I had had them all. And this was a much more satisfactory and accomplishing pain, I comforted myself.

I thought about famous men who wrote about childbirth such as Tolstoy and O’Neill and I thought, “What do they know about it, the idiots.” It gave me pleasure to imagine one of them in the throes of childbirth. How they would groan and holler and rebel. And wouldn’t they make everybody else miserable around them. And there I was, conducting a neat and tidy job.

The waves of pain became tidal waves. Earthquake and fire swept my body. Through the rush and roar of the cataclysm that was all about me, I heard the murmur of the doctor and the answered murmur of the nurse at my head. In a white blaze of thankfulness, I heard, faint about the clamor in my ears, a peculiar squawk. They handed my baby to me. I placed her on my full breast where she mouthed around, too lazy to tug for food. I thought, “What do you want, little bird? That it should run into your mouth, I suppose. But no, you must work for your provender already!”

No matter how cynically or casually the worldly may treat the birth of a child, it remains spiritually and physically a tremendous event. God pity the woman who does not feel the fear, the awe, and the joy of bringing a child into the world.

I was filled with awe of my baby’s new life and in gratitude to God, I wanted her to be baptized in the Catholic Church. I did not want my child to flounder as I had often floundered. I wanted to believe, and I wanted my child to believe, and if belonging to the Church would give her so inestimable a grace as faith in God, and the companionable love of the saints then the thing to do was to have her baptized a Catholic. This was the final straw for Forster who wanted nothing to do with any commitments or what he termed as my “absorption in the supernatural”.

I knew that I was going to have my child baptized a Catholic, cost what it may. I knew I was not going to have her floundering as I had done, doubting and hesitating, undisciplined and amoral. I felt it was the greatest thing I could do for my child.

So, Tamar was baptized in June. For myself, I prayed for the gift of faith. I was sure, yet not sure. I postponed the day of decision. To become a Catholic meant for me to give up a mate with whom I was much in love. It got to the point where it was the simple question of whether I chose God or man. I chose God and I lost Forster. I was baptized on the Feast of The Holy Innocents, December 28, 1927. It was something I had to do. I was tired of following the devices and desires of my own heart, of doing what I wanted to do, what my desires told me to do, which always seemed to lead me astray. The cost was the loss of the man I loved, but it paid for the salvation of my child and myself.

I painfully described this loss in The Long Loneliness: “For a woman who had known the joys of marriage, yes, it was hard. It was years before I awakened without that longing for a face pressed against my breast, an arm around my shoulder. The sense of loss was there. It was a price I had paid. I was Abraham who had sacrificed Isaac. And yet I had Isaac, I had Tamar.”

I always had a great regret for my abortion. In fact, I tried to cover it up and to destroy as many copies of The Eleventh Virgin as I could find. But my priest chided me and said, “You can’t have much faith in God if you’re taking the life given to you and using it that way. God is the one who forgives us if we ask, and it sounds like you don’t even want forgiveness, but just to get rid of the books.” I never forgot what the priest pointed out in the vanity or pride at work in my heart. Since that time, I wasn’t as worried as I had been. If you believe in the mission of Jesus Christ, then you’re bound to try to let go of your past, in the sense that you are entitled to His forgiveness. To keep regretting what was, is to deny God’s grace.

After my conversion, I struggled to support my child as a single parent working as a free-lance writer. In December 1932, I was in Washington D.C. covering the Hunger March of the Unemployed. Watching the ragged men marching moved my sense of social justice and I was inspired to go to the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception to pray. I cried out to God in anguish that some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor.

When I returned to New York, I found waiting for me an unkempt man with fire in his eyes. Immediately he began preaching to me in a thick French accent his grand vision for social justice. His name was Peter Maurin, and together we founded the Catholic Worker Movement.

We opened houses of hospitality for the poor, the hungry, the homeless, and for abused women and pregnant mothers. We practiced the spiritual and corporal works of mercy. One day thirty-year-old Elizabeth came to us at the end of her pregnancy. Her husband was a drug addict. It was New Year’s Eve, the eve of the Feast of the Holy Family. He came to our house drugged and sat at supper asleep while his wife fed him.

I called the ambulance but he refused their help. He muttered, “She’s my wife. She has to stick to me. She has to take care of me.” Oh, I thought, The distortion of the idea of the Holy Family. She has to take care of him and she about to bear his child! But we had a little bed ready for the baby, and a box of pretty garments, and she was happy as she looked at them, and there was even gaiety in our midst as we sat around the fire and had a cup of tea in the holiday spirit.

I’ll never forget the time that I had to literally stand up against birth control. My sister Della had worked for Margaret Sanger, foundress of Planned Parenthood. When Della exhorted me that I shouldn’t encourage my daughter Tamar to have so many children, I stood up firmly and walked out of the house, whereupon Della ran after me weeping, saying, “Don’t leave me, don’t leave me. We just won’t talk about it again.” To me, birth control and abortion are genocide. I say, make room for children, don’t do away with them. I learned that prevention of conception when the act that one is performing is for the purpose of fusing the two lives more closely and so enrich them that another life springs forth, and the aborting of a life conceived are sins that are great frustrations in the natural and spiritual order.

The Sexual Revolution is a complete rebellion against authority, natural and supernatural, even against the body and its needs, its natural functions of child bearing. This is not reverence for life, it is a great denial and more resembles Nihilism than the revolution that they think they are furthering.

Once I asked a man why he signed a petition for the Rosenbergs who had been convicted of treason in the fifties. “It is because I am against capital punishment,” he said. In other words, he, as the rest of us, is in favor of life – life until natural death.

I was happy that I could be with my mother the last few weeks of her life, and for the last ten days at her bedside daily and hourly. Sometimes I thought that it was like being present at a birth to sit by a dying person and see their intentness on what is happening to them. It almost seems that one is absorbed in a struggle, a fearful, grim, physical struggle, to breathe, to swallow, to live. And so, I kept thinking to myself, how necessary it is for one of their loved ones to be beside them, to pray for them, to offer up prayers for them unceasingly, as well as to do all those little offices one can.

When my daughter Tamar was a little tiny girl, she said to me once, “When I get to be a great big woman and you are a little tiny girl, I’ll take care of you.” I thought of that when I had to feed my mother by the spoonful and urged her to eat her custard. Shortly before she died, I told her, “We can no more imagine life beyond the grave than a blind man can imagine colors.” How good God was to me, to let me be there. I was there, holding her hand, and she just turned her head and sighed. That was her last breath, that little sigh; and her hand was warm in mine for a long time after.

Dorothy Day was the co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement. She is a model pro-life lay witness and intercessor. She was chosen as the 20th century’s most outstanding lay Catholic. Cardinal John O’Connor of New York introduced the cause for her canonization and said, “It is with great joy that I announce the approval of the Holy See for the Archdiocese of New York to open the Cause for the Beatification and Canonization of Dorothy Day. With this approval comes the title Servant of God. What a gift to the Church in New York and to the Church Universal this is!”

Dorothy Day, Servant of God, pray for us – for us who labor for a culture of life and a civilization of love, for the unborn, for the mothers in crisis pregnancies, for mothers who have suffered from abortions, for the poor and for the dying.